The following is the second part of the true and tragic story about Dave Shaw’s failed attempt to to recover the dead body of Deon Dreyer who never returned from Bushman’s Hole. His body was found by Dave Shaw ten years later on a world-record dive to 271 Meters, the bottom of Bushman’s cave.

This part describes the unlucky happening on December 17, 1994 when Deon Dreyer did not return to the surface to be found by Shaw 10 years later.

Raising the dead – part 2

DEEP-WATER DIVERS have always been the daredevils of the diving community, pushing far into the dark labyrinths of water-filled holes and extreme ocean depths. It’s a small global fraternity—there are no more than a dozen members—and in the history of recreational diving, only six people other than Shaw have ever pulled off successful dives below 820 feet. (More people have walked on the moon, Don Shirley likes to point out.) At least three ran into serious trouble in the process (including Nuno Gomes, who got stuck in the mud on the bottom of Bushman’s Hole for two minutes before escaping). And two have since died: American Sheck Exley, who drowned while diving the world’s deepest sinkhole, Mexico’s 1,080-foot-deep Zacatón, in April 1994; and Britain’s John Bennett, who disappeared while diving a wreck off the coast of South Korea in March 2004.

“Today extreme divers are far exceeding any reasonable physiology capabilities,” says American Tom Mount, a pioneer in technical diving and the owner of the Miami Shores, Florida–headquartered International Association of Nitrox and Technical Divers (IANTD). “Equipment can go to those depths, but your body might not be able to.”

Aside from the dangers of getting trapped or lost, breathing deep-dive gas mixes—usually a combination of helium, nitrogen, and oxygen known as trimix—at extreme underwater pressure can kill you in any number of ways. For example, at depth, oxygen can become toxic, and nitrogen acts like a narcotic—the deeper you go, the stupider you get. Divers compare narcosis to drinking martinis on an empty stomach, and, depending on the gas mix you’re using, at 800-plus feet you can feel like you’ve downed at least four or five of them all at once. Helium is no better; it can send you into nervous, twitching fits. Then, if you don’t breathe slowly and deeply, carbon dioxide can build up in your lungs and you’ll black out. And if you ascend too quickly, all the nitrogen and helium that has been forced into your tissues under pressure can fizz into tiny bubbles, causing a condition known as the bends, which can result in severe pain, paralysis, and death. To try to avoid getting the bends, extreme divers spend hours on ascent, sitting at targeted depths for carefully calculated periods of decompression to allow the gases to flush safely from their bodies. As divers say, if you do the depth, you do the time.

About Bushman’s Hole

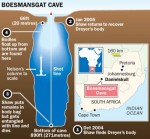

For any diver who can stomach the risks, Bushman’s Hole is world-class. It’s located on the privately owned Mount Carmel game farm, 11,000 acres of rolling, ocher-earthed veldt sparsely thatched with silky bushman grass and dotted with sun-baked termite mounds. Not until you top a small rise a few miles from the farm dwellings do you notice a break in the clean sweep of the land, where the earth starts to fall in on itself as if a giant hammer had come smashing down. The resulting crater is hundreds of feet from rim to rim and walled on one side by a sheer cliff. If you hike down the steep, stony path on the opposite side, you come to a small, swimming-pool-size basin of water, covered in a green carpet of duckweed. This is the entrance to Bushman’s Hole.

No one had any idea how deep Bushman‘s was until Nuno Gomes arrived. On his first visit, in 1981, the Johannesburg-based Gomes dived to almost 250 feet, dropping down through a narrow chimney that opens up into an enormous chamber below 150 feet. In 1988, he set an African depth record of just over 400 feet, and Bushman’s reputation as a deep diver’s cave started to spread. In 1993, Sheck Exley showed up. Supported by a team that included Gomes, Exley became the first diver to hit bottom, touching down at 863 feet on the hole’s sloping floor.

No one had any idea how deep Bushman‘s was until Nuno Gomes arrived. On his first visit, in 1981, the Johannesburg-based Gomes dived to almost 250 feet, dropping down through a narrow chimney that opens up into an enormous chamber below 150 feet. In 1988, he set an African depth record of just over 400 feet, and Bushman’s reputation as a deep diver’s cave started to spread. In 1993, Sheck Exley showed up. Supported by a team that included Gomes, Exley became the first diver to hit bottom, touching down at 863 feet on the hole’s sloping floor.

During the Exley expedition, Gomes performed a sonar scan of the hole. It revealed Bushman’s to be the largest freshwater cave ever discovered, with a main chamber that was approximately 770 feet by 250 feet across and more than 870 feet deep. (Gomes later found a maximum depth of at least 927 feet.)

Diving Bushman’s is exhilarating. The narrow entrance is claustrophobic, but once you reach the vast main chamber, it’s like spacewalking. For a young cave diver like Deon Dreyer, it must have been irresistible. Deon grew up in the modest town of Vereeniging, about 35 miles south of Johannesburg, and loved adventure in all its forms. He shot his first buck at the age of ten. By 17 he was racing a souped-up car around local tracks, tinkering with his motorcycle, and designing obscenely loud car stereos. Another of his passions was diving. “He couldn’t sit still, never, ever, ever,” says his younger brother, Werner, now 27.

Deon Dreyer

Deon had logged about 200 dives when he was invited to join some South Africa Cave Diving Association divers at Bushman’s Hole over the 1994 Christmas break. They planned a descent to 492 feet and asked Deon to dive support. He was thrilled. Two weeks before the expedition, Deon’s grandfather passed away. Sitting around a barbecue with his family one night, Deon spoke with boyish hubris. “He said if he had a choice of how to go out in life, he’d like to go out diving,” recalls his father, Theo, 51, the owner of a business that sells and services two-way radios.

Deon’s mother, Marie, a petite 50-year-old, begged Deon not to go. In 1993, Bushman’s Hole had already taken the life of a diver named Eben Leyden, who blacked out at 200 feet. (A dive buddy rushed him to the surface, but Leyden didn’t survive.) And then, on December 17, 1994, the hole claimed Deon Dreyer.

For Marie and Theo, the nightmare started with a policeman’s knock at the door. They rushed to Mount Carmel, where slowly the story came out. The team had been doing a practice dive. On the way back up, at 196 feet, Deon appeared to be fine, exchanging hand signals with his buddy. The group continued ascending. At 164 feet they suddenly noticed a light below them. A quick, confused diver count came up one short. Team leader Dietloff Giliomee wasn’t sure what was happening. Then another diver, in the eerie glow of his submersible light, dragged his finger across his throat. Giliomee desperately started swimming down but stopped when he realized the light below him was already more than 100 feet deeper and fading fast. “I decided it was a suicide chase,” he wrote in the accident report.

No one knows for sure what killed Deon. The best guess is deep-water blackout from carbon dioxide buildup. Two weeks after the accident, Theo paid to bring in a small, remotely operated sub used by the De Beers mining company. It found Deon’s dive helmet on the vast floor of Bushman’s, but there was no sign of his body. Resigning themselves to the idea that Deon would stay in the hole for eternity, Theo and Marie placed a commemorative plaque on a rock wall above the entry pool. “He had the most majestic grave in the country,” Theo says. “And I said, ‘Well, this will be his final resting place.’ ”

But on October 30, 2004, Dave Shaw called Theo and said, “I will go and fetch your son.” Theo immediately responded, “Yes, absolutely yes.” More than anything, he realized, he wanted to see his boy again.